L'ingrédient manquant dans la technologie supply chain : la confiance

Pourquoi les planificateurs font plus confiance aux tableurs qu’aux systèmes ? Découvrez comment la transparence et l’explicabilité rétablissent la...

Cessez de réagir à des prévisions obsolètes et commencez à vous aligner sur la demande réelle.

Intuiflow aide les industriels à réduire leurs stocks, améliorer leur taux de service et reprendre le contrôle, avec des résultats en quelques semaines, pas en trimestres. Le tout sans complexité.

Brent Mosley

Directeur de la chaîne d'approvisionnement chez Flogistix

grâce à une visibilité en temps réel et à des buffers alignés sur la demande qui réduisent les surstocks.

grâce au réapprovisionnement piloté par la demande, à une réponse plus rapide à la variabilité.

en alignant le réapprovisionnement, les achats et les opérations sur ce qui est réellement nécessaire, au moment exact où c’est nécessaire..

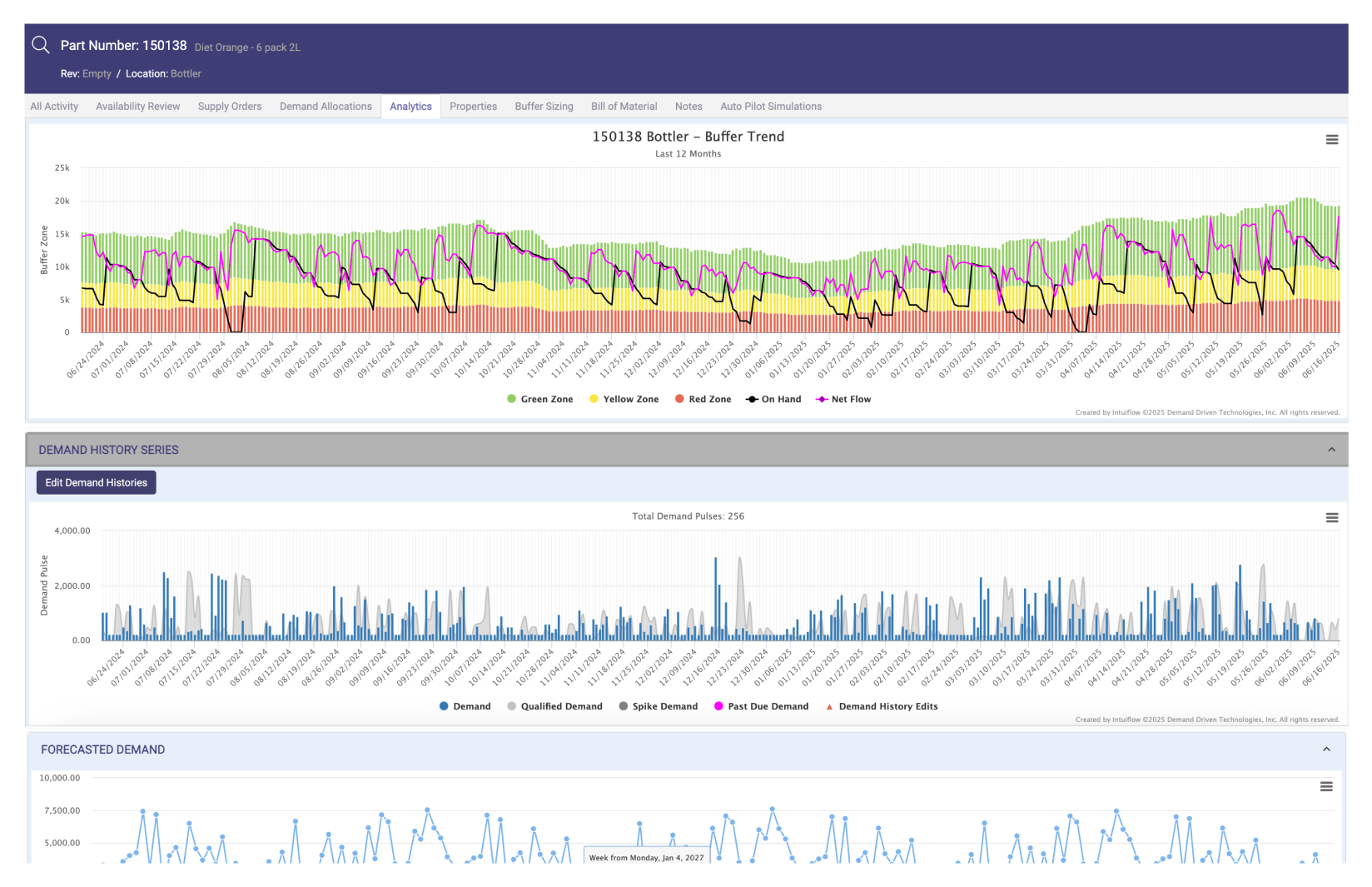

Intuiflow capte la demande réelle, ajuste dynamiquement les buffers et priorise automatiquement ce qui compte le plus dans votre supply chain.

Propulsé par le DDMRP, il remplace les plans statiques par un modèle vivant qui se met à jour en temps réel et réagit avec clarté.

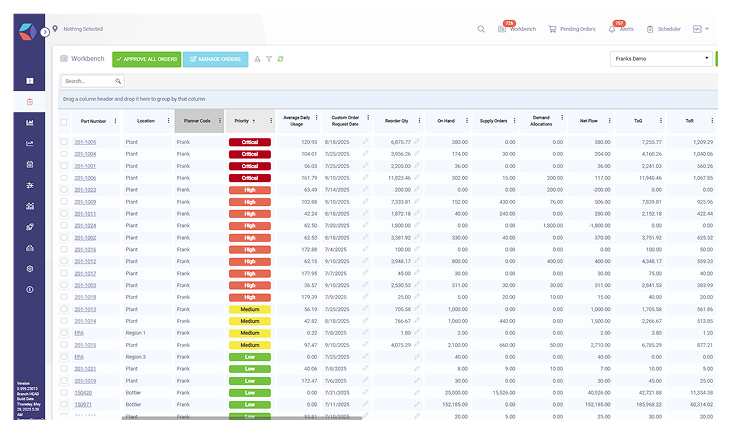

Offrez à vos équipes une vue en direct, par rôle, de la performance des buffers, des signaux de demande et des risques d’approvisionnement.

Les planificateurs ajustent les priorités, les responsables S&OP orientent les décisions, et les dirigeants suivent les niveaux de service sans attendre de rapport.

De l'atelier à l'équipe de direction, tout le monde travaille à partir de la même vérité issue du système.

POUR PLANIFIER

Intuiflow remplace les hypothèses « la prévision prime » par des signaux en temps réel, cadencés par la consommation réelle.

Obtenez chaque jour une vision claire de ce qu’il faut commander, quand et pourquoi.

POUR LES ÉQUIPES DE PRODUCTION

Intuiflow transforme les signaux de demande changeants en priorités claires, tenant compte des capacités, sur lesquelles vos équipes peuvent agir.

Résultat : moins de reprogrammations, moins d'en-cours, et un flux plus rapide sur l’atelier.

POUR LES RESPONSABLE DE S&OP

Bénéficiez d’une vue partagée des priorités, des signaux de demande et de l’état de santé du flux dans l’ensemble de votre supply chain.

Notre tour de contrôle intégrée détecte les risques avant qu’ils ne s’aggravent et alimente des simulations qui font avancer votre processus S&OP.

POUR LES RESPONSABLES DES OPÉRATIONS

Auto Pilot ajuste dynamiquement le buffer de chaque article en fonction de la demande réelle et des objectifs de service.

Vous réduisez les excès, évitez les ruptures et prenez des décisions en toute confiance, basées sur la réalité du terrain.

POUR LES GESTIONNAIRES DE STOCK

Auto Pilot permet d'aligner les stocks sur la demande réelle sans travail manuel. Il ajuste dynamiquement les seuils de réapprovisionnement à l'aide de données en temps réel, fait apparaître les exceptions qui comptent et vous permet de simuler des changements avant de vous engager, afin que votre chaîne d'approvisionnement reste légère, réactive et sous contrôle.

Voir le module Auto PilotUNE INTELLIGENCE INTÉGRÉE QUI POUSSE À L'ACTION

La Business Intelligence (BI) intégrée d’Intuiflow transforme les données de planification en direct en informations clés exploitables, qui permettent des décisions, en temps réel.

Identifiez les causes racines, lancez des simulations et agissez sur ce qui compte vraiment sans attendre le support IT ni jongler avec des tableaux de bord déconnectés.

Le processus d'intégration rapide d'Intuiflow s'appuie sur des simulations pour garantir des paramètres optimaux et fournir rapidement des résultats mesurables.

Pourquoi les planificateurs font plus confiance aux tableurs qu’aux systèmes ? Découvrez comment la transparence et l’explicabilité rétablissent la...

Découvrez pourquoi intégrer la planification par les flux dès votre projet ERP accélère votre transformation.

Découvrez comment les boucles de contrôle PID, Kanban et Demand Driven optimisent les flux et la régulation des systèmes industriels et logistiques.

Et découvrez ce qu'Intuiflow peut faire pour votre équipe.