What is the normal demand for a product, and what’s atypical?

How can we size stocks according to demand variability and account for spikes in demand?

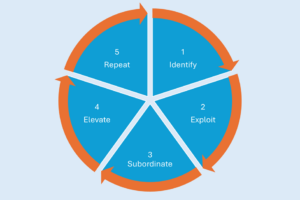

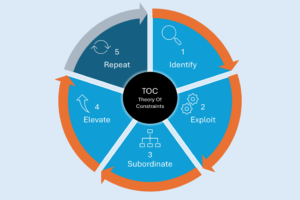

These issues do not date back to the advent of DDMRP. However, DDMRP gives them a new framework by integrating the notion of “qualified demand” into the net flow equation that triggers a replenishment order.

The consideration of this “qualified demand” clearly differentiates a DDMRP buffer from a conventional control point or a kanban, which typically only reacts to actual consumption.

Bringing Demand Spikes into the Flow

There are three components of “qualified demand.”

- Backorders

- Requirements for today

- Demand spikes in the future

By integrating peaks of future demand—demands that could eventually disappear or change—the flow equation incorporates a reasoned risk. Of course, failing to anticipate these demands could also put us at risk, so it is important to take them into account.

This spike detection mechanism is often the subject of many questions when DDMRP models are designed. What is the detection threshold to be used? What is the detection horizon? What is the relationship between the size of the red zone and spike detection? What is the visibility horizon available on firm requirements?

In our experience, it is necessary to carry out some experiments to find the right setting. Simulations based on demand history allow us to ask good questions, and critical analysis of demand spikes during model tuning allows us to adjust the firing.

Planning For Demand Variability

The first question to ask ourselves is: what is the “normal” demand that I should be able to meet with a short lead time from available stock?

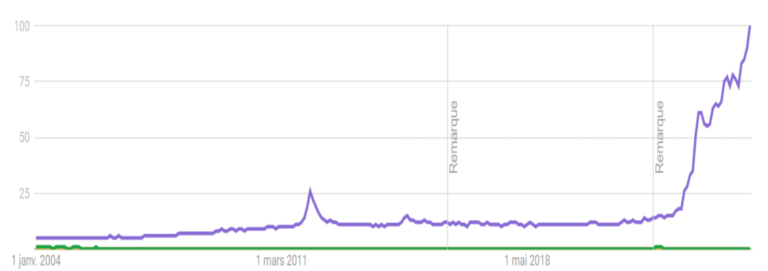

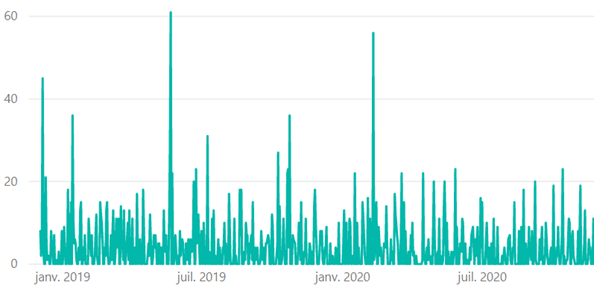

Let’s take the example of the article presenting the below demand history :

It is clear that there are spikes in demand, happening about once a month.

When we exclude these spikes, the demand is as follows:

The question is: should my DDMRP buffer be designed to meet the entire demand, including spikes, or just this “base” demand?

The difference between the two options represents for this single item a stock investment of 10k€.

The answer will depend on our knowledge of the business context.

Do these peaks, when orders are received, need to be shipped immediately, or do we receive these orders in advance? If we know about them on a given horizon, we could react to them using spike detection. If not, we have no choice but to take them into account to size the red zone. In the first case, we should take these peaks into account for the calculation of the ADU. In the second case, it is better to exclude them.

For this example, after analysis, it turned out that the spikes on this item were caused by a downstream distribution center within the company, which had set up a monthly replenishment from the hub whose demand history we see. The solution was to switch to a weekly replenishment in VMI mode, greatly reducing the variability of demand and therefore the inventory requirements on the hub. Beware about self-induced variability!

The data analysis algorithms help us to detect these situations, but it is the knowledge of the teams that will allow us to define the right design of the model. In other words: you will need to adjust over time.

Calibrating Spike Detection

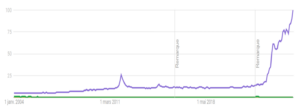

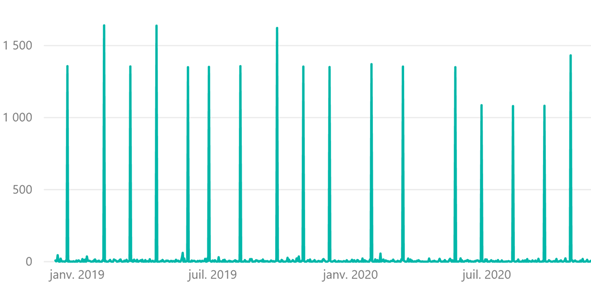

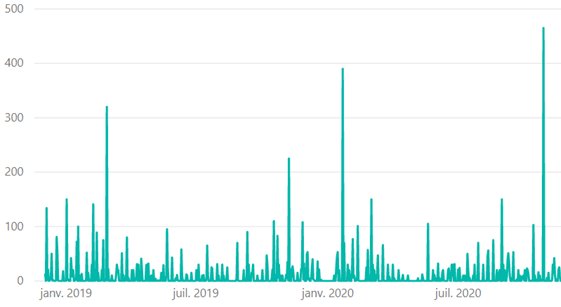

In the case below, we will privilege a setting whose spike detection is around 200, which will lead us to detect 4 peaks over a period of 2 years.

Here are some tips to help you in calibrating spike detection:

- When we detect a spike, we react “to order” to that event, and thus transmit the variability of the demand to our supplier/production. So the more spikes we detect, the more variability and stress we convey upstream.

- Conversely, the more we cover demand variability with the red zone, the more we calm the game down… but we increase the inventory investment.

- Make sure that “normal” demand is covered by the red zone on your strategic items. For example, demand on a component that is triggered by parent items manufacturing orders is driven by the lot sizes of those parent materials. The red zone should cover these requirements without spike detection.

- Make sure, on a daily basis, that spikes in demand are analyzed by planners. A spike indicates an atypical demand. An atypical demand should induce a decision: should I negotiate a delivery schedule with my customer, should I ship out my inventory at the risk of jeopardizing other demands, should I ask my supplier for an effort?

- Identify the frequency of spikes per item, and review the items with frequent spikes in your DDS&OP routines.

- On long lead times, shorten the peak detection horizon; on short lead times, lengthen it (including beyond the decoupled lead time, especially if your capacity is constrained).

- The convention, which works in many cases, is to detect sikes at 50% of the red zone. This threshold can often be increased to make the model less nervous.

The correct setting of spike detection requires a little experimentation and should be part of continuous improvement efforts. This process will give you a better understanding of your daily demand, and therefore opportunities to reduce the variability of your demand.