Is inventory management just about avoiding shortages?

In the vast majority of companies, the primary role of buyer/planners is to avoid shortages. If you supply components for an assembly plant, production will be on your back for every shortage — it prevents manufacturing, and the line may be shut down! If you’re supplying finished goods inventory, your sales team will be quick to react if key revenue generating products are out of stock. Your mailbox, your phone, and your Teams should be able to testify of the exchanges on the subject.

Therefore, there is strong social pressure from your peers in the company to avoid stock outs at all costs.

Conventional control systems are also focused on the subject. You have to respect a safety stock and do what it takes to maintain it. You must respect a lower stock limit for each item. Much more rarely, an upper limit will be defined.

Unpacking Inventory Management Metrics

Tell me how I am measured, as the saying goes, and you will understand how I act. In my experience, the individual objectives of procurement or planning staff are often focused on availability, number of shortages, service rate. Sometimes, executives focus on cost compliance, but more rarely on inventory turns, and even more rarely on the risks of excess and obsolescence.

The dashboards reflect this: The number of shortages, backorders, the aging of delays, the service rate and compliance with the production schedule are all part of the managerial rituals.

There is nothing wrong with these indicators, but they all induce a cognitive bias: Too little is much worse than too much.

Firming up requirements beyond the item’s replenishment time — to anticipate just in case, ordering a larger lot than required, so you don’t have to go back and maybe trigger a discount — is largely acceptable, and sometimes even encouraged.

Starting work orders too early to ensure that there is plenty of work on the shop floor, that production perceives the pressure of volume, that it will heat up the machines, and will be able to group campaigns. Of course, there is nothing wrong with that!

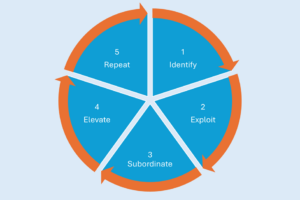

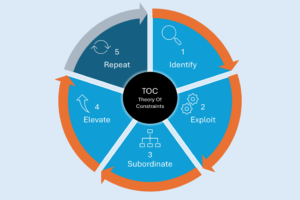

Defining An Upper Limit, Or, The Invisible Big Blue

In Demand Driven approaches, an upper limit is defined. Above this limit, we are in the blue. If you order beyond the lead time, it’s blue. If we order more than required, it’s blue. If we start a WO in advance, it’s blue.

When we start to paint the excesses in blue, we discover in most companies a big blue that was invisible until then! Very commonly more than 1/3 of the items sit there, and it is unknown.

It’s not fair to say that once a year we had excess and obsolescence reviews with the Finance team, where we looked at this blue… only to find that there was nothing left to do about it.

By making this blue visible, by integrating it into dashboards and team discussions, we discover opportunities and causalities that were previously under the radar.

Generating blue is consuming the capacities and materials of the company and its suppliers to make useless things, to the detriment of useful things. Generating excess on some references leads to shortages on other references. Releasing WOs too early means that the workshop will manufacture those to the detriment of others that will finish late. Too much generates too little!

The increased visibility allows for process improvements to be initiated. We can ask on the spot, “Why do you want to order this, when it’s pushing us into the blue?” We can also structurally restrict the replenishment and release process — and thus ensure that excesses are only generated by exception, deliberately, after risk analysis and model adaptation. We move from a reactive mode to a proactive mode.

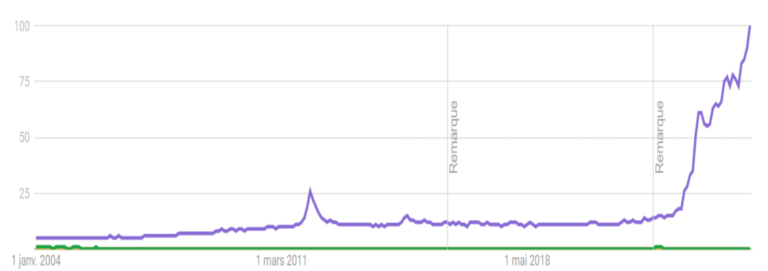

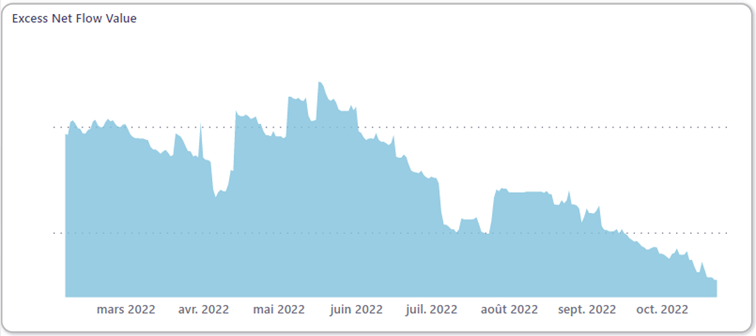

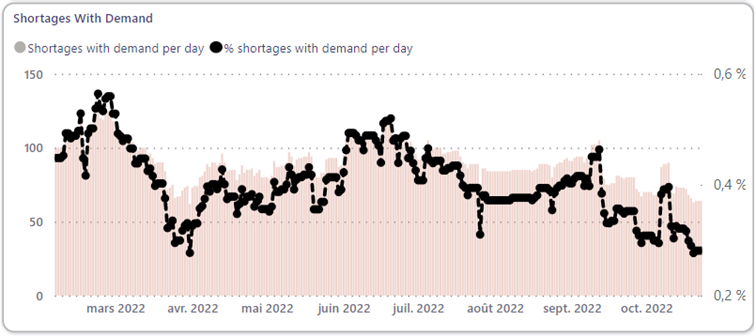

Below is an example from a company that made its big blue visible.

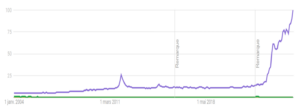

Volumes ordered above the high limit have vanished:

Shortages are down:

Inventory turns are increasing… with plenty of room for improvement

If you also want to tap into your big blue opportunities, do not hesitate to contact us!